Recently, I’ve been participating in some of the BSides Joint Task Force CTF challenges. This CTF is being put on by the organizers of the recent BSides Chicago and upcoming BSides Detroit. They’re spanning both conferences, and also releasing challenges online in between.

I thought I’d do a write up of one of these challenges, since it’s both a fun exercise and the way I solved it makes a good introduction to Ruby. If you’re never used Ruby, I encourage you to give it a try. It’s a powerful language, and I find it’s syntax to be extremely intuitive. Of course, there’s a number of ways to solve this challenge.

I’ll try to outline not only my path to solving this, but also some failed ideas, in the hopes that they’ll shed some light on my thought process.

Thanks to the BSJTF and especially to @dth0m for putting this challenge together.

The Challenge

For this challenge, we’re given a file and told it contains an IP address that is our flag. I didn’t save the full text, but that’s the basic challenge.

Getting started

The first thing we need to do is find out what kind of file we’re working with. For this, we turn to the trusty ‘file’ command.

$ file whatinzeus

whatinzeus: tcpdump capture file (little-endian) - version 2.4 (Ethernet, capture length 65535)

So we know we have a packet capture. The next step is to take a look at it and see what it contains. For this, I turn to Wireshark.

Wireshark Analysis

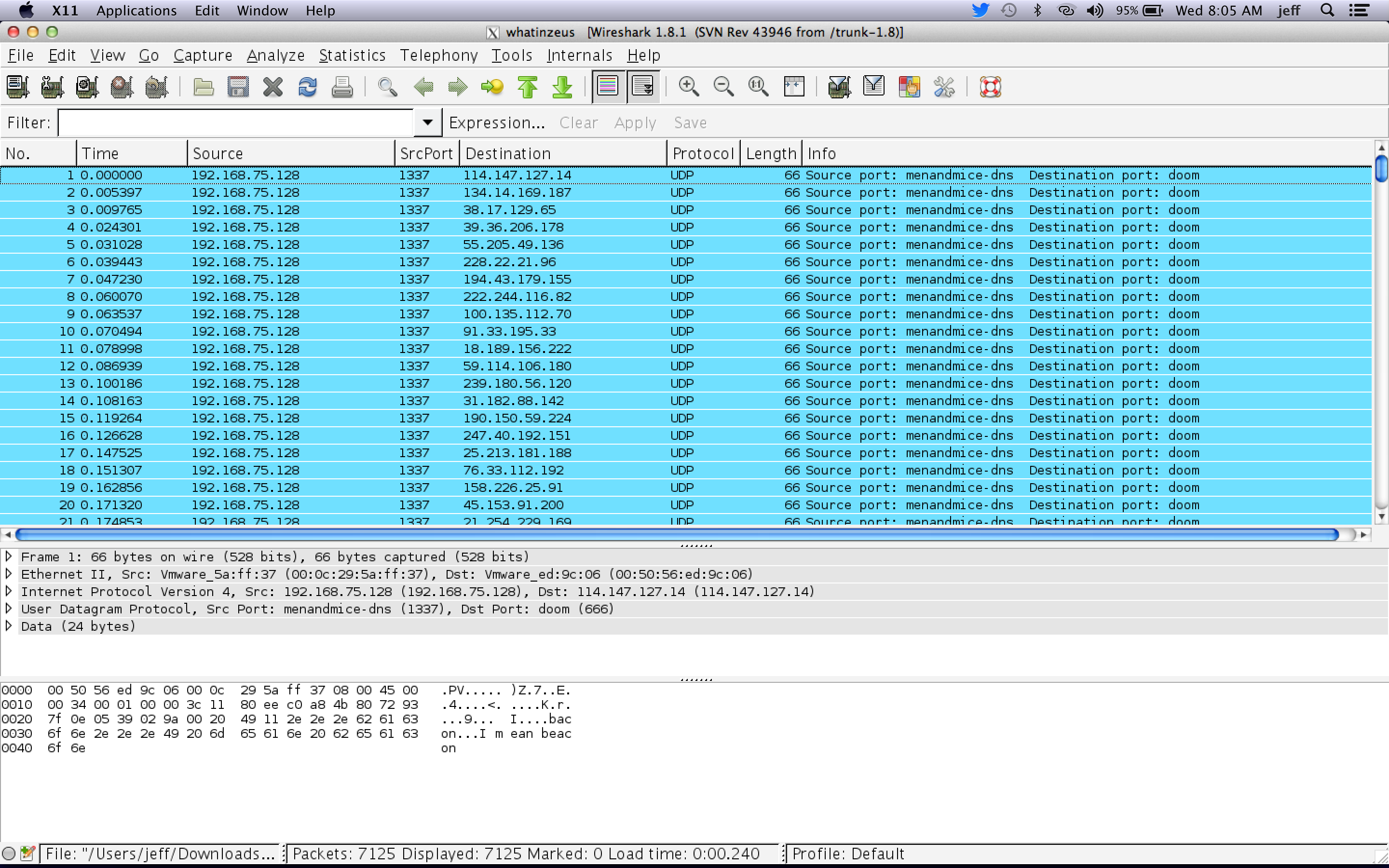

Opening the file in Wireshark, we see something like this:

The file contains 7125 packets, and at a glance they look fairly similar. All of them we look at are UDP packets which seem to originate from the same source IP on port 1337. They’re destined for various addresses, but consistently using destination port 666. The length of the packets also seems consistent at 66 bytes.

The file contains 7125 packets, and at a glance they look fairly similar. All of them we look at are UDP packets which seem to originate from the same source IP on port 1337. They’re destined for various addresses, but consistently using destination port 666. The length of the packets also seems consistent at 66 bytes.

Near the bottom of the screen, we see the payload of the first packet, which again matches the others. The UDP payload contains only the string “…bacon…I mean beacon”

We can try some filters to see if all the packets match this pattern, or if there are any outliers that may point us to the key. Some of the things I tried were: ip.src != 192.168.75.128 udp.dstport != 666 udp.length != 32 udp contains “…bacon…I mean beacon”

Each of these returns zero packets, except the last which returns our original 7125. This confirms that all follow the patterns we’ve identified from a cursory glance.

Regroup

So far, we know that our packets are mostly identical, with only a few differences. It’s likely these differences will lead us to the flag, so let’s try to isolate them and compile a list of what’s likely to be interesting.

Scrolling through packets with the arrow keys, and watching Wireshark’s ‘Packet Details’ window points out another difference. Most of the packets are destined for the same MAC address on Layer 2, which is probably the default gateway, but some are destined for multicast MACs. This strikes me as an interesting difference.

So, thinking about the differences between packets we have:

- Layer 2 Multicast

- Destination IP address

- Timestamp

Let’s look at these in reverse order:

Timestamp

The Timestamp deltas might be something, but we can see they’re fairly consistent and very fast. There doesn’t seem to be enough variation here to encode any kind of information.

Destination IP Address

These change, but since all hosts are receiving identical traffic there doesn’t seem to be much to go on.

Layer 2 Multicast

This becomes my primary focus. It seems to be a way of flagging various packets as different. My initial thoughts center around this being a binary encoding scheme where multicast packets represent 1 and unicast represent 0. I decide to pursue this avenue.

First Attempt

I promised you some ruby, and here’s where we get into it. I needed a way to parse the pcap, and build a binary string where each bit’s value is determined by whether or not the destination MAC of the corresponding packet is multicast. Ruby, and specifically the packetfu gem make this easy.

Packetfu was written by Tod Beardsley @todb, who many of you might know from his work on Metasploit. It’s a ruby gem that makes packet manipulation, sniffing, and pcap analysis really simple. If you’re familiar with Python’s scapy, packetfu is similar. It doesn’t have quite the same degree of application-layer protocol support, but for our purposes it’s ideal.

I prefer Ruby over Python for a number of reasons. Not the least of this is that it’s interactive shell, irb, is well suited to working with objects (like our pcaps) in real time. I find Python’s whitespace sensitivity especially annoying when coding interactively, and for this sort of task that’s exactly what I do. I often keep IRB up in one window so I can probe and maniuplate data, while Sublime Text in another window acts as a clipboard and notepad for my results. Often, when I solve the challenge what I’m left with in Sublime is pretty close to an stand alone script.

To get started, we install the packetfu gem using the command gem install packetfu then launch IRB irb

Now we require packetfu (and ipaddr which we’ll use later), and create an array of packets from our capture file ``` ruby Require gems, parse packet capture require ‘packetfu’ require ‘ipaddr’

packets = PacketFu::PcapFile.read_packets(‘./whatinzeus’)

A lot of output scrolls by, as PacketFu shows us a string representation of each packet. The realy beauty is that we have an array of packets, and all of Ruby's enumerable methods are available to us.

By filtering in Wireshark for "eth.ig == 1" we find that all the multicast packets in our pcap (and there's 509 of them) have an ethernet vendor ID (the most significant three bytes of the MAC) of 01:00:5e.

So, we can use ruby's [Enumerable::inject](http://ruby-doc.org/core-2.0/Enumerable.html#method-i-inject) method to build an array of bits, where 1 is set when the MAC begins with these bytes.

``` ruby Build a binary array

output = packets.inject([]){|ret, pkt|

ret.push(PacketFu::EthHeader.str2mac(pkt.eth_dst) =~ /^01:00:5e/ ? 1 : 0)

}

Inject can be a little odd for begining ruby programmers. Essentially what it’s doing is passing an accumulator (called ret in our case) along with each packet (pkt) to a block delimited by {}. We initialize ret as an anonymous array, the [] parameter to inject. The block pushes a value to the ret array, which is determined by a ternary operation in (). The ternary in this case converts the packet’s ethernet destination address to a string, and compares to the regex in // delimiters which indicates a string must start with 01:00:5e to be true. If it’s true, it’ll return a 1 and if false a 0. After the last packet is processed, inject returns the contents of the ret. The ret array (which is now technically an anonymous array is then assigned to our ‘output’ variable.

If that’s not entirely clear, it might help to think of it in a less optimized form. The code above is equivilant to ``` ruby A longer way, but maybe a little easier to follow output = []

packets.each{|pkt| pkt_string = PacketFu::EthHeader.str2mac(pkt.eth_dst)

if pkt_string =~ /^01:00:5e/ then

output.push(1)

else

output.push(0)

end

} ```

However we get there, output should contain 7125 elements, and 509 of them should be 1’s. ``` ruby Some sanity checks in irb 1.9.3-p125 :227 > output.count => 7125 1.9.3-p125 :228 > output.find_all{|x| x == 1}.count => 509 1.9.3-p125 :229 > output.find_all{|x| x == 0}.count => 6616

From here, we convert the bit array to binary, and write it to a file. I'll save you all the details, and just poing you to Ruby's [Array:pack](http://ruby-doc.org/core-2.0/Array.html#method-i-pack) and [String:unpack](http://ruby-doc.org/core-2.0/Array.html#method-i-unpack) Together, they allow us to convert strings to arrays and vice versa, accounting for the various encodings.

In any case, this method ends up with complete gibberish. I mostly shared it so I'd have an excuse to explain inject, because it's useful later :)

TL;DR for this section - the Multicast MACs are just an artificat of a UDP packet being generated for a multicast IP address. In other words, it's just the lower layer fulfilling what was asked at at higher layer; I missed that nugget and spent some time chasing this theory. Ohh well...

## Second Attempt

So, with dst mac as binary encoding ruled out, what else do we have? Well, remember before that IP addresses vary. They look fairly random at a glance, but just how random are they? How many different IPs are represented in the capture?

``` ruby Number of occurences for each IP

ip_counts = packets.inject(Hash.new(0)){|ret, pkt| ret[pkt.ip_dst] += 1; ret}

...

ip_counts.keys.uniq.count

=> 7125

Again we use inject, but this time inserting a hash with a default value of 0 as our accumulator. This let’s us treat the hash value as an Integer, since it will already be initialized, and just add to it within the block. We end up with a hash where the key is an IP value (in decimal notation) and the value is the number of times that IP address was observed.

The count tells us we have as many entries in our hash as we had packets, so there’s no IPs that repeat.

Rethinking…

Let’s think through this again. There’s been references to malware behaviors both in the Zeus reference in the name, and the payload mentioning a beacon. Why would malware spray UDP like this if that’s what this is meant to be? Well, it could be a means of masking it’s true Command and Control server by spraying the same data all over the place. Hiding in the crowd, as it were. With this in mind, I get interested in any patterns in the destination IPs themselves.

So let’s parse the IPs themselves

ips = packets.inject([]){ |ret, pkt|

ret << IPAddr.new(pkt.ip_dst, Socket::AF_INET).to_s.split(".")

}

...

1.9.3-p125 :034 > ips[0]

=> ["114", "147", "127", "14"]

Our old friend inject is back, and this time we’re building an array. Within the block, we pull the ip_dst from the packet, and make it into an IPAddr object. We take the string (dotted decimal) representation, and split it into an array, so each octet is a seperate string. We view the first IP to confirm we have an array of arrays, where the outer index is the packet number, and the inner index is the octet number.

Let’s look at this a different way. There’s four octets per IP, so let’s build an array of the values for each octet.

octets = []

(0..3).each{|i|

octets[i] = []

ips.each{|x| octets[i] << x[i]}

}

Now, octets[0] is an array containing the first octect of each IP, where it’s index is the packet number. For example, if we wanted to see the first octet of each of the first 5 IPs

octets[0][0,5]

=> ["114", "134", "38", "39", "55"]

This makes it easy to view the number of unique values in each octet position: ``` ruby Unique occurences of each octet puts “#{octets[0].uniq.count} #{octets[1].uniq.count} #{octets[2].uniq.count} #{octets[3].uniq.count}”

This outputs "250 256 255 255" telling us there's 250 values in the first octet, 256 in the second, and 255 in both the 3rd and fourth. This is _very_ interesting. Since each byte could have a value in the range of (0..255), it's clear we're missing some values, especially in the first octet.

So the obvious question is "What's missing?" Let's find out:

``` ruby Finding missing octet values

(0..3).each{|x|

puts "Octet #{x}"

(0..255).each{|y|

puts y unless octets[x].include?(y.to_s)

}

puts ""

}

Here we have two .each iterators. The first goes through the range of octets (0 through 3) while the inner loop goes through each possible octet value. The puts statement just prints that inner value, if our octets array doesn’t include that value in the corresponding octet’s array. Notice it cast’s the octet value (y) to a string before checking, since we kept our octets array as strings rather than integers.

The output is telling: ``` text Output Octet 0 0 10 127 169 172 192

Octet 1

Octet 2 0

Octet 3 0

Octet 0 is missing some values that are immediately recognizable as reserved IP space. 1 has the full range of possible values, while the last two octets are both missing 0.

This leads to the theory that our 'malware' is generating IPs but skipping private IP space (the reserved class A's demonstrated by the first octet values), as well as IPs with 0 in any octet. This makes some sense, since the 0 values would likely be network IPs if we confine ourselves to classful subnet boundaries.

But why is there a 0 in the second octet?

Let's see what IP has a zero in the second octet.

``` ruby Finding IP with 0 in second octet

ips.find{|ip| ip[1] == "0"}.join(".")

=> "37.0.122.152"

Since we’re looking for an IP as a flag, I try this an sure enough it works.

Challenge solved!

Here’s a script that runs through some of these steps.

``` ruby whatinzeus_solve.rb require ‘packetfu’ require ‘ipaddr’

puts “– Reading packets” packets = PacketFu::PcapFile.read_packets(‘./whatinzeus’)

output = packets.inject([]){|ret, pkt| ret.push(PacketFu::EthHeader.str2mac(pkt.eth_dst) =~ “01:00:5e” ? 1 : 0) }

puts “\n– Parsing IPs” ips = packets.inject([]){|ret, pkt| ret « IPAddr.new(pkt.ip_dst, Socket::AF_INET).to_s.split(“.”) }

octets = [] (0..3).each{|i| octets[i] = [] ips.each{|x| octets[i] « x[i]} }

puts “\n– Unique occurences of each octet” puts “#{octets[0].uniq.count} #{octets[1].uniq.count} #{octets[2].uniq.count} #{octets[3].uniq.count}”

puts “\n– What’s missing from each?” (0..3).each{|x| puts “Octet #{x}” (0..255).each{|y| puts y unless octets[x].include?(y.to_s) } puts “” }

puts “\n– Hmmm… nothing with 0 in the second octet?” puts “\tThis one has a 0:\t\t\n#{ips.find{|ip| ip[1] == “0”}.join(“.”)}”

puts “\n–Done.”

## Epilogue

After the challenge closed, my friend [Trey](http://www.twitter.com/trey_underwood) shared a better way. As it turns out, the packet whose dest was the flag also had a smaller TTL. I can't believe I missed this, but I did... :( This makes sense in a scenario where the packet might not have been built using the typical UDP/IP stack on the host, and is a pretty good sign of a crafted packet (unless it took far more hops before our collection point that the other packets.)

This method makes for a much simpler solve. Here's an IRB/Packetfu solve based on TTL.

``` ruby Easier way - TTL... ugh!

1.9.3-p125 :001 > require 'packetfu'

=> true

1.9.3-p125 :002 > packets = PacketFu::PcapFile.read_packets('./whatinzeus')

<lots of output>

1.9.3-p125 :003 > packets.inject(Hash.new(0)){|ret, pkt| ret[pkt.ip_ttl] += 1; ret}

=> {60=>7124, 20=>1}

1.9.3-p125 :003 > IPAddr.new(packets.find{|pkt| pkt if pkt.ip_ttl == 20}.ip_dst, Socket::AF_INET).to_s

=> 37.0.122.152"